Clustering and decision tree

On the final day of my statistics training I learnt clustering and decision tree. The funny thing about these 2 topics is I learnt the algorithms in my computer science class but was never taught how to apply them to real world problems. That’s what I’m doing today.

Clustering

Clustering is good for uncovering unknown groupings in a data set. It is primarily a descriptive technique to help ask further questions in future analysis. The following table lists several countries with their numerical scores on several measures:

| Country | Literacy | Infant mortality | Birth rate | Death rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 95 | 25.6 | 20 | 9 |

| Australia | 100 | 7.3 | 15 | 8 |

| Bolivia | 78 | 75 | 34 | 9 |

| Cameroon | 54 | 77 | 41 | 12 |

| Chile | 93 | 14.6 | 23 | 6 |

| China | 78 | 52 | 21 | 7 |

| Costa Rica | 93 | 11 | 26 | 4 |

| Egypt | 48 | 76.4 | 29 | 9 |

| Ethiopia | 24 | 110 | 45 | 14 |

| Greece | 93 | 8.2 | 10 | 10 |

| Haiti | 53 | 109 | 40 | 19 |

| India | 52 | 79 | 29 | 10 |

| Indonesia | 77 | 68 | 24 | 9 |

| Italy | 97 | 7.6 | 11 | 10 |

| Kenya | 69 | 74 | 42 | 11 |

| Kuwait | 73 | 12.5 | 28 | 2 |

| Mexico | 87 | 35 | 28 | 5 |

| Nicaragua | 57 | 52.5 | 35 | 7 |

| Nigeria | 51 | 75 | 44 | 12 |

| Phillippine | 90 | 51 | 27 | 7 |

| Somalia | 24 | 126 | 46 | 13 |

| Thailand | 93 | 37 | 19 | 6 |

| USA | 97 | 8.1 | 15 | 9 |

| Vietnam | 88 | 46 | 27 | 8 |

| Zambia | 73 | 85 | 46 | 18 |

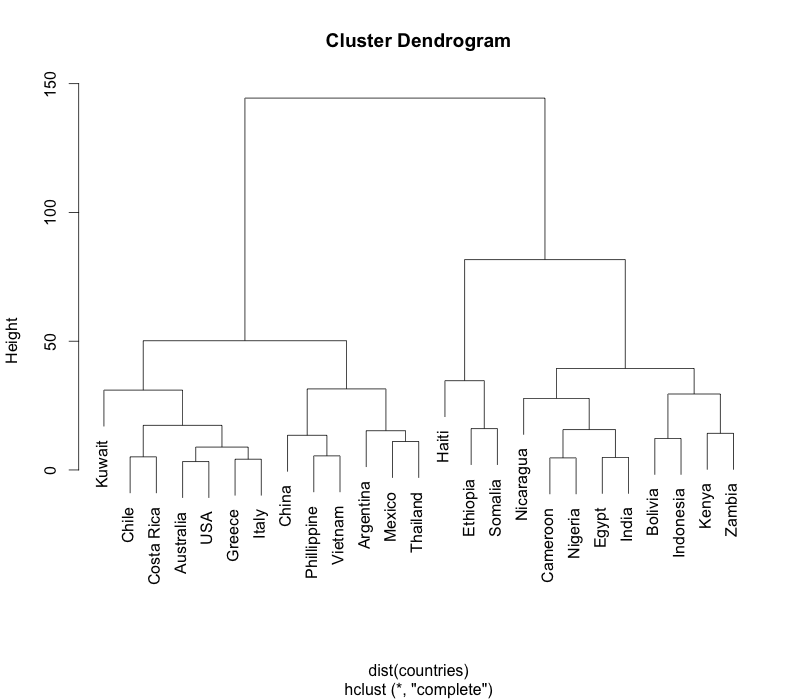

One way to group data is hierarchical clustering. The result is a dendrogram.

> countries <- read.csv("countries.csv", row.names=1)

> clusters <- hclust(dist(countries))

> plot(clusters)

>

The hclust function has many clustering algorithms. Changing the algorithms sometimes produces surprising insights. A dendrogram is great for people to visualise the cluster, but if we want the clusters in numerical form we can do this:

> cut <- cutree(clusters, k=4)

> data.frame(countries, cut)

Literacy Infant.mortality Birth.rate Death.rate cut

Argentina 95 25.6 20 9 1

Australia 100 7.3 15 8 2

Bolivia 78 75.0 34 9 3

Cameroon 54 77.0 41 12 3

Chile 93 14.6 23 6 2

China 78 52.0 21 7 1

Costa Rica 93 11.0 26 4 2

Egypt 48 76.4 29 9 3

Ethiopia 24 110.0 45 14 4

Greece 93 8.2 10 10 2

Haiti 53 109.0 40 19 4

India 52 79.0 29 10 3

Indonesia 77 68.0 24 9 3

Italy 97 7.6 11 10 2

Kenya 69 74.0 42 11 3

Kuwait 73 12.5 28 2 2

Mexico 87 35.0 28 5 1

Nicaragua 57 52.5 35 7 3

Nigeria 51 75.0 44 12 3

Phillippine 90 51.0 27 7 1

Somalia 24 126.0 46 13 4

Thailand 93 37.0 19 6 1

USA 97 8.1 15 9 2

Vietnam 88 46.0 27 8 1

Zambia 73 85.0 46 18 3

> The k=4 argument to cutree says we want 4 clusters. It’s easily verified from the dendrogram. Alternatively, starting from the dendrogram, we can specify a height. For example, cutting the dendrogram at height 60 will yield 3 clusters (a horizontal line y=60 will cut through 3 lines).

> cut <- cutree(clusters, h=60)

> data.frame(countries, cut)

Literacy Infant.mortality Birth.rate Death.rate cut

Argentina 95 25.6 20 9 1

Australia 100 7.3 15 8 1

Bolivia 78 75.0 34 9 2

Cameroon 54 77.0 41 12 2

Chile 93 14.6 23 6 1

China 78 52.0 21 7 1

Costa Rica 93 11.0 26 4 1

Egypt 48 76.4 29 9 2

Ethiopia 24 110.0 45 14 3

Greece 93 8.2 10 10 1

Haiti 53 109.0 40 19 3

India 52 79.0 29 10 2

Indonesia 77 68.0 24 9 2

Italy 97 7.6 11 10 1

Kenya 69 74.0 42 11 2

Kuwait 73 12.5 28 2 1

Mexico 87 35.0 28 5 1

Nicaragua 57 52.5 35 7 2

Nigeria 51 75.0 44 12 2

Phillippine 90 51.0 27 7 1

Somalia 24 126.0 46 13 3

Thailand 93 37.0 19 6 1

USA 97 8.1 15 9 1

Vietnam 88 46.0 27 8 1

Zambia 73 85.0 46 18 2

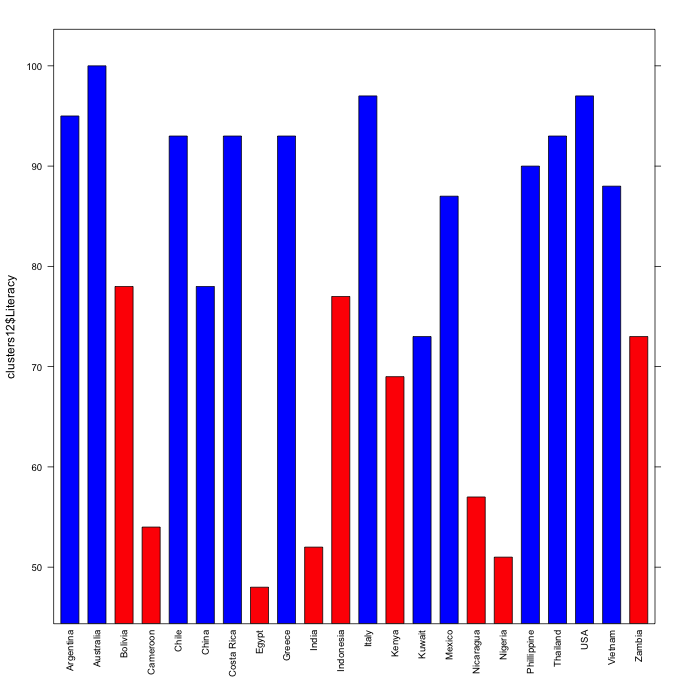

> Next, we want to see how clusters 1 and 2 differ. Let’s trim the cluster table down a bit.

> countries <- data.frame(countries, cut)

> clusters12 <- countries[countries$cut %in% c(1,2), ]

> clusters12

Literacy Infant.mortality Birth.rate Death.rate cut

Argentina 95 25.6 20 9 1

Australia 100 7.3 15 8 1

Bolivia 78 75.0 34 9 2

Cameroon 54 77.0 41 12 2

Chile 93 14.6 23 6 1

China 78 52.0 21 7 1

Costa Rica 93 11.0 26 4 1

Egypt 48 76.4 29 9 2

Greece 93 8.2 10 10 1

India 52 79.0 29 10 2

Indonesia 77 68.0 24 9 2

Italy 97 7.6 11 10 1

Kenya 69 74.0 42 11 2

Kuwait 73 12.5 28 2 1

Mexico 87 35.0 28 5 1

Nicaragua 57 52.5 35 7 2

Nigeria 51 75.0 44 12 2

Phillippine 90 51.0 27 7 1

Thailand 93 37.0 19 6 1

USA 97 8.1 15 9 1

Vietnam 88 46.0 27 8 1

Zambia 73 85.0 46 18 2

>

> cols <- c("red", "blue")

> col_pos <- clusters12$cut == 1

> barchart(clusters12$Literacy ~ rownames(clusters12), col=cols[col_pos+1], scales=list(x=list(rot=90)))

>

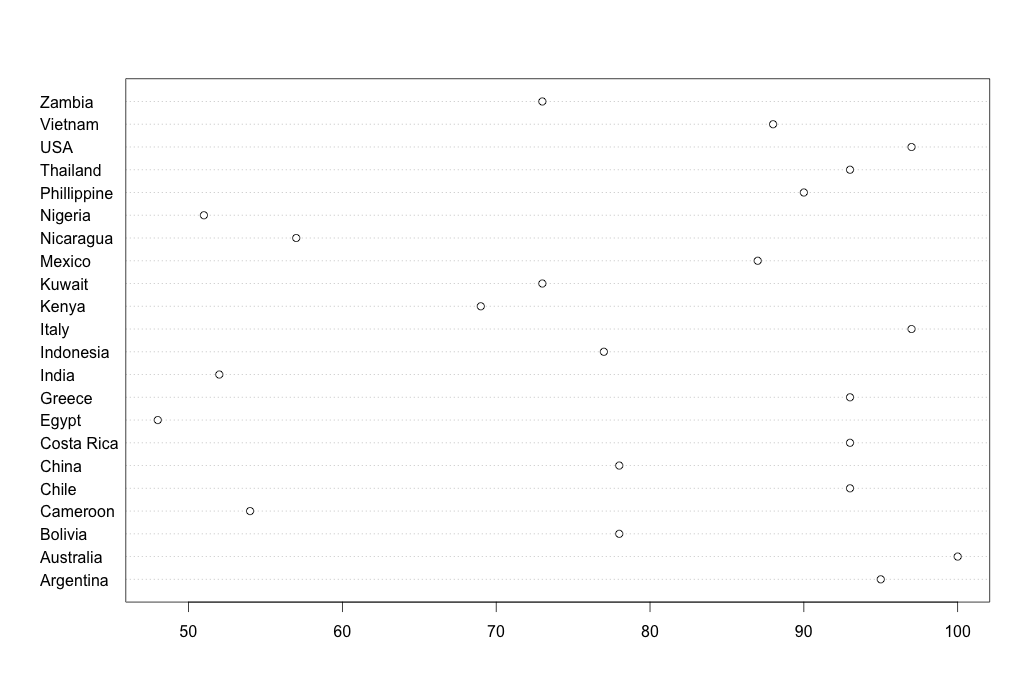

It becomes quite clear that clusters 1 and 2 differ in their literacy rates. A dot chart reveals further clustering:

> dotchart(clusters12$Literacy, labels=rownames(clusters12))

Our 2-cluster data table actually contains 3 clusters! The dot chart shows there are high literacy countries such as Australia and Italy; middling ones such as China and Indonesia; and lowly-literate ones like Egypt and India. A picture tells a thousand words indeed. The point of clustering and the different charts is really to discover hidden patterns in the data. When we start to find homogeneity as we go into a cluster (all the highly-literate countries, say), it becomes useful to explore other dimensions such as infant mortality.

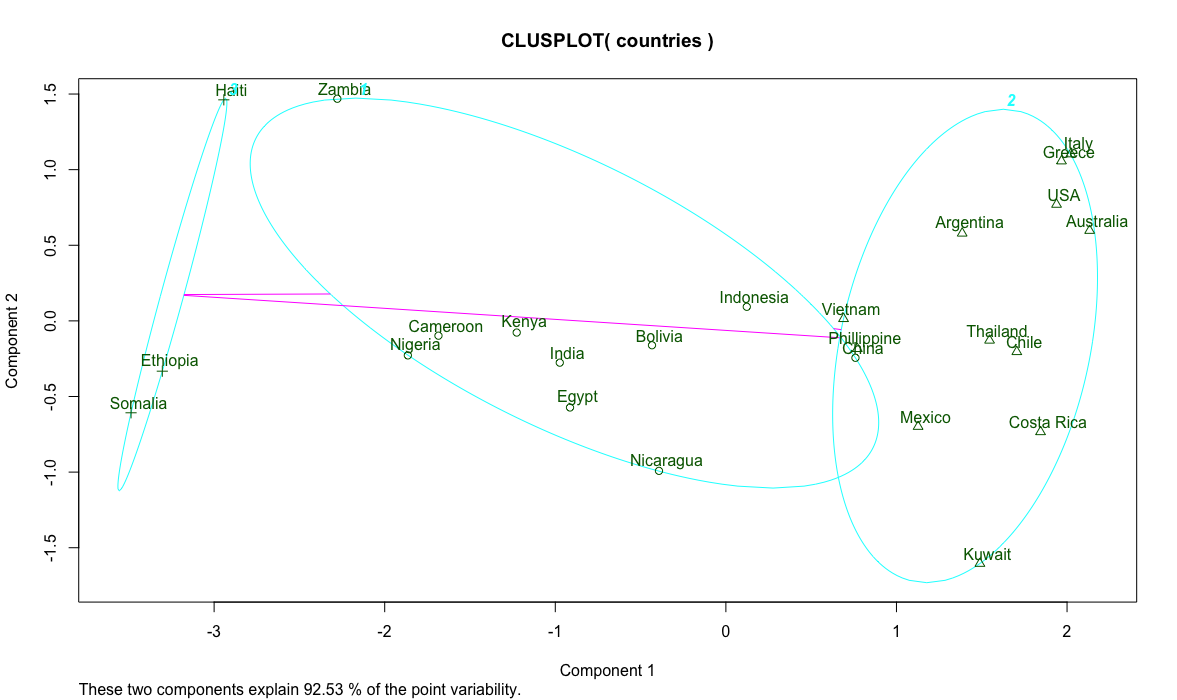

Another way of clustering data is K-means clustering.

> countries <- read.csv("countries.csv", row.names = 1)

> library(cluster)

> fit <- kmeans(countries, 3)

> fit

K-means clustering with 3 clusters of sizes 10, 12, 3

Cluster means:

Literacy Infant.mortality Birth.rate Death.rate

1 63.70000 71.39000 34.50000 10.40000

2 91.58333 21.99167 20.75000 7.00000

3 33.66667 115.00000 43.66667 15.33333

Clustering vector:

Argentina Australia Bolivia Cameroon Chile China Costa Rica Egypt Ethiopia

2 2 1 1 2 1 2 1 3

Greece Haiti India Indonesia Italy Kenya Kuwait Mexico Nicaragua

2 3 1 1 2 1 2 2 1

Nigeria Phillippine Somalia Thailand USA Vietnam Zambia

1 2 3 2 2 2 1

Within cluster sum of squares by cluster:

[1] 3227.889 3992.236 784.000

(between_SS / total_SS = 82.6 %)

Available components:

[1] "cluster" "centers" "totss" "withinss" "tot.withinss" "betweenss" "size"

[8] "iter" "ifault"

> clusplot(countries, fit$cluster, labels = 2)

>

The magic here is the kmeans function that produces the specified 3 clusters we wanted. It has several algorithms to figure out a formula to describe the data columns and find the centroid of each record. The things to watch out for are cohesion of points within a cluster and separation of clusters. In our country list, Vietnam, Phillipines and China are ambiguous. Further analysis can help guide the clustering effort.

Decision tree

In this exercise we use the bank loan data sets. The first, the training set, is a historical data set of borrower data and their known default status. In other words, a group of people who’ve borrowed money and whether they defaulted the loan. We want to understand what causes borrowers to default.

> loan <- read.csv("bankloanTrain.csv")

> head(loan)

age ed employ address income debtinc creddebt othdebt default

1 41 3 17 12 176 9.3 11.359392 5.008608 1

2 27 1 10 6 31 17.3 1.362202 4.000798 0

3 40 1 15 14 55 5.5 0.856075 2.168925 0

4 41 1 15 14 120 2.9 2.658720 0.821280 0

5 24 2 2 0 28 17.3 1.787436 3.056564 1

6 41 2 5 5 25 10.2 0.392700 2.157300 0

> Most columns are easy to understand but some takes a bit of explaining. ed is an ordinal attributes with 1 meaning below high school completion to 5 representing a post graduate degree. It follows that you can use their Euclidean distance to find how different people are even though strictly speaking the difference is not linear. employ and address represent number of years spent in the current employment and home address, respectively. income, creddebt and othdebt are all dollar amount in thousands, and debtinc is debt to income percentage.

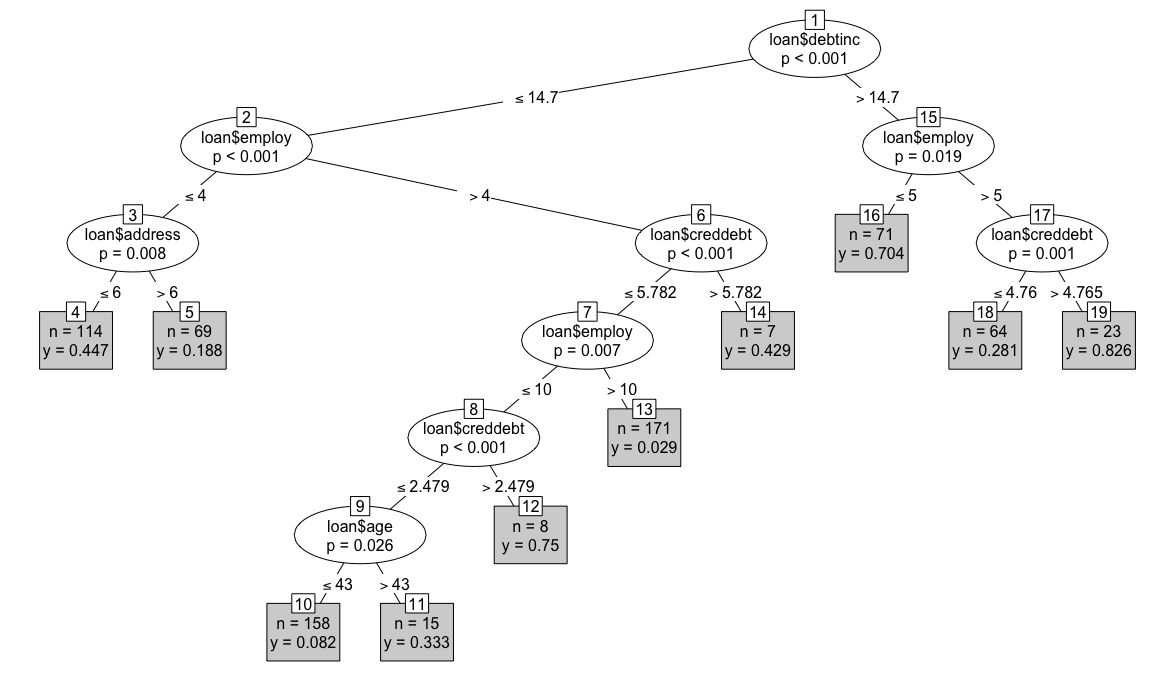

Our aim is to use the training set of 700 records to predict how likely a future borrower will default. First, we construct a decision tree.

> library(party)

> loan_ctree <- ctree(loan$default ~ loan$age + loan$ed + loan$employ + loan$address + loan$income + loan$debtinc + loan$creddebt + loan$othdebt)

> loan_ctree

Conditional inference tree with 10 terminal nodes

Response: loan$default

Inputs: loan$age, loan$ed, loan$employ, loan$address, loan$income, loan$debtinc, loan$creddebt, loan$othdebt

Number of observations: 700

1) loan$debtinc <= 14.7; criterion = 1, statistic = 106.086

2) loan$employ <= 4; criterion = 1, statistic = 51.874

3) loan$address <= 6; criterion = 0.992, statistic = 10.72

4)* weights = 114

3) loan$address > 6

5)* weights = 69

2) loan$employ > 4

6) loan$creddebt <= 5.781564; criterion = 0.999, statistic = 15.664

7) loan$employ <= 10; criterion = 0.993, statistic = 11.026

8) loan$creddebt <= 2.47904; criterion = 1, statistic = 21.439

9) loan$age <= 43; criterion = 0.974, statistic = 8.613

10)* weights = 158

9) loan$age > 43

11)* weights = 15

8) loan$creddebt > 2.47904

12)* weights = 8

7) loan$employ > 10

13)* weights = 171

6) loan$creddebt > 5.781564

14)* weights = 7

1) loan$debtinc > 14.7

15) loan$employ <= 5; criterion = 0.981, statistic = 9.193

16)* weights = 71

15) loan$employ > 5

17) loan$creddebt <= 4.76476; criterion = 0.999, statistic = 14.473

18)* weights = 64

17) loan$creddebt > 4.76476

19)* weights = 23

> plot(loan_ctree, type="simple")

>

We can see that people who have defaulted most are those with a high debt-to-income ratio (> 14.7), staying at the same job for more than 5 years and has a high credit card debt (leaf node 19 on the right). Intuitively it makes sense. Although staying in a job shows stability, in this case it’s more likely that those borrowers are stuck in their job because of their high debt. Age, education and other factors don’t count as long as you have much debt. n=23 in the box means there’re 23 such borrowers in our training data set, representing 82.6% of this sub-population. It’s easy to see the least-likely to default borrowers are those with low debt, long current employment (> 10) and little credit card debt (leaf node 13). There’re 171 such borrowers in the training set and only 2.9% of them defaulted. The percentage can also be seen as the likelihood of someone fitting this profile defaulting. In other words, someone fitting the profile of a safe borrower has a 2.9% chance of defaulting.

Once we have fitted our training data to a tree, we can use the tree to predict new data. In our test data set, we have 150 loan applicants:

> test <- read.csv("bankloanTest.csv")

> head(test)

age ed employ address income debtinc creddebt othdebt

1 36 1 16 13 32 10.9 0.544128 2.943872

2 50 1 6 27 21 12.9 1.316574 1.392426

3 40 1 9 9 33 17.0 4.880700 0.729300

4 31 1 5 7 23 2.0 0.046000 0.414000

5 29 1 4 0 24 7.8 0.866736 1.005264

6 25 2 1 3 14 9.9 0.232848 1.153152

> We want to see the default likelihood of each applicant. To do so, we use the predict function:

> p <- predict(loan_ctree, test)

> head(p)

default

[1,] 0.02923977

[2,] 0.33333333

[3,] 0.82608696

[4,] 0.08227848

[5,] 0.44736842

[6,] 0.44736842

> test$default <- p

> head(test)

age ed employ address income debtinc creddebt othdebt default

1 36 1 16 13 32 10.9 0.544128 2.943872 0.02923977

2 50 1 6 27 21 12.9 1.316574 1.392426 0.33333333

3 40 1 9 9 33 17.0 4.880700 0.729300 0.82608696

4 31 1 5 7 23 2.0 0.046000 0.414000 0.08227848

5 29 1 4 0 24 7.8 0.866736 1.005264 0.44736842

6 25 2 1 3 14 9.9 0.232848 1.153152 0.44736842

> You can verify using the tree the first row in the test data set is a safe borrower. Hence, our prediction model scores this applicant with a 2.9% defaulting risk.

The trick to using a decision tree is to realise some factors are correlated. Oftentimes, a bit of domain knowledge will help spot and verify such correlations, which can be removed from the model.